USYD essays on DAUGHTERS OF THE DUST (SFF 1992) and HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR (SFF 2014)

In 2023, the University of Sydney and Sydney Film Festival joined forces in a new partnership supporting the Living Archive website and the ongoing preservation of our film culture. Contributions to the Living Archive will continue the legacy of a festival born of and with continuing connection to its community. To celebrate this shared history: four new critical reflections by USYD scholars have been added to the Archive. You can read them below.

Reclaiming Memory: The Role of Speculative Fiction in Daughters of the Dust

By Madiba Doyle-Lambert

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) both utilises and explores the capacity of speculative fiction to preserve cultural memories, while simultaneously producing new cultural materials that can inform future remembrances of cultures historically eroded by colonial oppression. As the Gullah Peazant family prepare to immigrate from Igbo Landing to mainland USA, legacies of slavery, sensory cultural practices and narrative coalesce to construct a speculative fiction that responds to the United States’ legacy of slavery

Dash employs tactile auditory and sensory imagery to audiovisually capture cultural memories that have survived through oral tradition. In constructing a speculative fiction, she creates avenues of remembering knowledge otherwise rendered inaccessible by the hands of colonial oppression. Shortly after the film’s midpoint, several generations of the Peazant family gather at the beach to celebrate the cultural memories contained at Igbo Landing, while also contemplating their prospective future on the mainland United States.

Figure 1.

During this celebration, Dash presents a sequence of close ups on family members as they hold and serve food (Figure. 1). A soundscape of laughter and cutlery clinking erupts as the camera zooms in past bodies, explicitly emphasising the food, saturating the screen with imagery and sound bound with sensory experience. Close-up shots of hands engaged in physical tasks — whether dyeing garments, or holding food— evoke sensory experiences that are frequently linked to the transmission of cultural memory. This crucial link between the senses and memory is furthered by the cross-cutting between old and young hands, suggesting a physical handing down of traditions through generations by the enactment of them. By emphasising gustatory knowledge through sensory imagery—specifically the hands that prepare and consume food—Dash intricately weaves historical African recipes and customs into the fabric of her speculative fiction, offering audiences imagery that recalls and celebrates cultural practices systematically dismissed by Western historiography. As Laura Marks notes, “in the absence of other records, food becomes… a vehicle of memory,” (Laura U. Marks, “The Memory of the Senses,” in The Skin of the Film Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Duke University Press: Durham , 2000), 225.) which Dash then preserves through cinema. Thus, Dash’s creation of Daughters as a work of speculative fiction illustrates the mode’s distinctive ability to safeguard knowledge that has been undermined by colonial legacies.

Dash’s deviation from Hollywood conventions redefines the role of speculative fiction, transforming it from a mere repository of oppressed epistemologies into a source of substantial cultural materials, offering new cinematic possibilities. Julia Erhart characterises Hollywood films as a “hegemonic imaging system,” (Julia Erhart, “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction,” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 13, no. 2 (May 1, 1996), 124.) whose conventions dictate the “standard of social realism,” (Ibid. 121.) thereby shaping societal memories and expectations. Operating within this influential yet exploitative Western industry, Dash utilises speculative fiction to present images that build upon cultural memories to challenge prevailing standards of social realism.

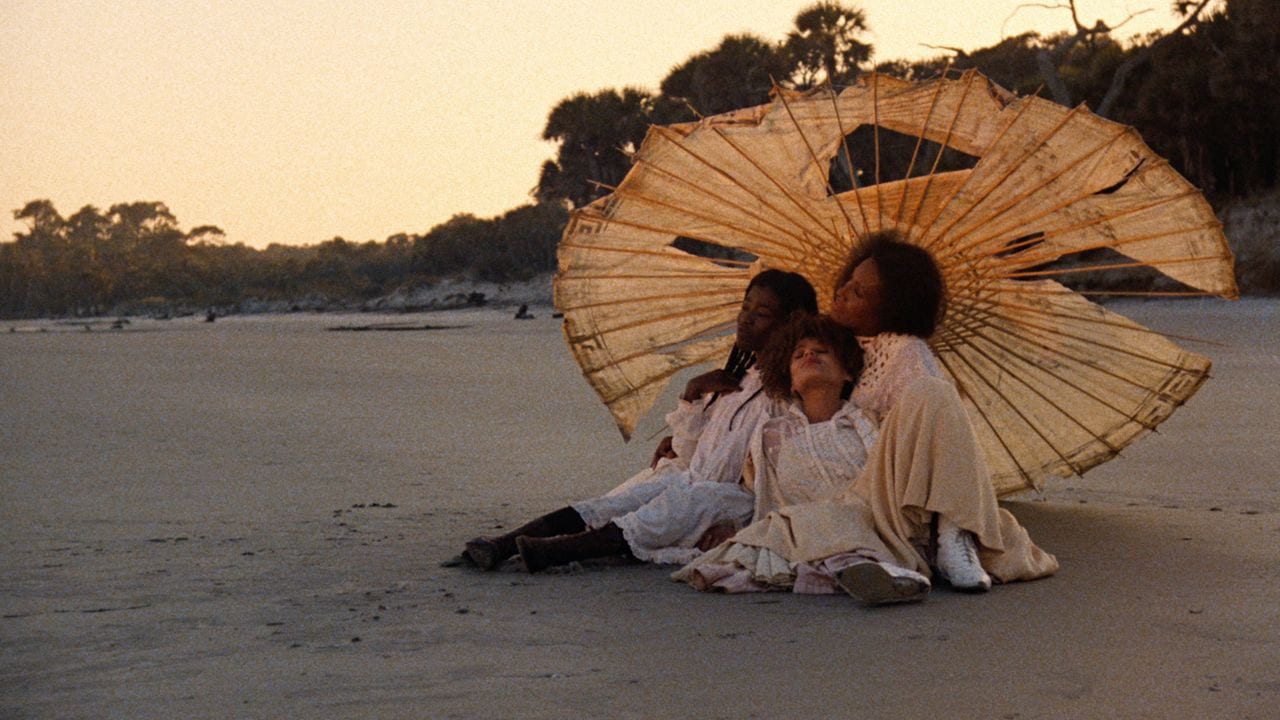

Figure 2.

Emerging from a dissolve transition from Figure. 1, a wide shot gradually pans across the beach, unveiling a carefully staged tableau of the Peazant family relaxing on a sand dune (Figure. 2). The mise-en-scène of this shot differs from classical cinema, which “hierarchises…with the effect of relegating people-of-colour to the frame’s margins.” (Erhart, “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction,” 126.) In contrast, Dash presents an image devoid of embedded social hierarchies, presenting a space and frame populated by and alive with Black bodies. Particularly, the arrangement of the Gullah women as centre frame contests Hollywood expectations of patriarchs commanding the most powerful space on frame. Dash’s use of deep focus prevents any single character from assuming narrative authority, while the panning action underscores the shot’s political defiance, slowly revealing a transcendence of hegemonic cinematic possibilities in order to “amend dominant conceptions of historiography.”(Ibid. 118) By positioning characters to gaze at the camera, she reverses the roles of subject and spectator, inviting viewers to reevaluate their understanding of history and the forces that shape it. Figure 2 represents new cultural material emerging from Dash’s speculative fiction. It challenges inadequate colonial histories by repurposing cinematic conventions to constitute an image essential for future remembrances of African cultures and history.

The speculative fiction in Daughters of the Dust intricately connects and preserves cultural memory through sensory experiences, illustrating how the intertwined nature of memory and the senses facilitates cultural reclamation.

Figure 3.

Just prior to the previously discussed celebration scene, the image of a Gullah man pushing his bike through sand accompanied by a child running alongside (Figure. 3), blends tactile imagery and cultural memory, creating a visual metaphor that recalls the past as much as it informs the future. The camera’s tracking of the man’s hunched posture and slow, forceful steps conveys the tactile strength and effort needed to push the bike through the sand, visually representing the challenge of preserving cultural memories that have been persistently degraded by colonial oppression. In a voiceover, Nana explains that although colonisers “didn’t keep good records,” the injustices of slavery were preserved through the memories of African griots, who, like Nana, served as oral historians. Her recounting of the inhumane actions forced upon slaves provides “a link to images of an African past,” (Erhart, “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction,” 119.) establishing continuity between the family’s devastating history and hopeful present. When viewed alongside Figure 3, the man’s act of pushing becomes a politically charged action within this continuity. Emerging from cultural memories of historical struggles, the present generation advances Gullah customs, despite the sands of history, so that future generations may progress with a memory of their ancestors’ constraints, yet unencumbered by them. This poignant visual metaphor enmeshes memory with tactile experience, not only to commemorate the injustices overcome by the Gullah people but also to articulate the continuity of the present and future with these histories. Dash’s use of speculative fiction articulates how each push against the legacies of slavery affords certain privileges, yet present generations must persist in remembering by continuing to push forward for the sake of future generations.

Dash utilises editing to engage in a meta-fictional analysis of how narrative practises, encompassing both oral histories and speculative fiction, facilitate the decolonization and reclamation of historical narratives. Erhart’s observation that Dash uses cutaways to indicate “associations between disparate problems or themes” (Ibid. 127.) is especially pertinent to Dash’s meta-fictional discourse.

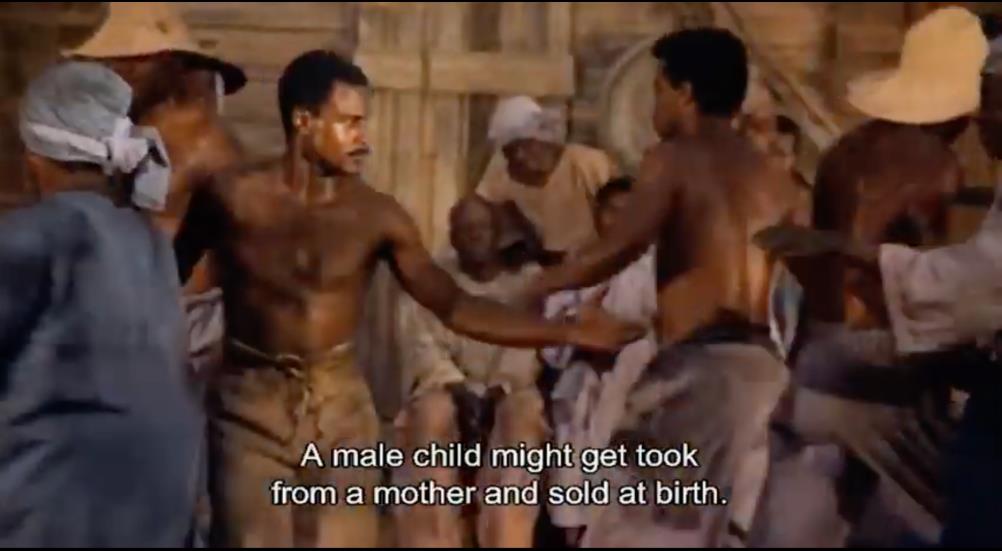

Figure 4.

During Nana’s speech, the image of the man with the bike is preceded by shots of slaves being exhibited at a sale (Figure. 4), which dissolves into a static shot of griots appearing to recount these stories. While the editing suggests historical continuity among the struggles depicted in each image, it is the enactment of narrative that facilitates remembrance. Thus, narrative practice itself can be understood as enabling the survival of cultural memory, by continuously producing new cultural materials. However despite this, the mise-en-scène of the slave sale contrasts significantly with the rest of the film. Dressed in the dirtied costumes and bathed in the studio lighting typical of Hollywood depictions of slavery, the image contrasts sharply with Nana’s oral history. This discrepancy arises because the image visualises Hollywood’s narratives rather than Gullah narratives. By placing the bike-metaphor after an image from the objectifying Hollywood gaze, Dash asserts that in the modern era, the true struggle of systematic oppression lies in the narratives and memories constructed by Hollywood and other perpetrators of structural racism. Thus, Dash meta-fictively cautions on the power of narrative in shaping memories of the past. In doing so, she provides a new cultural narrative that leverages cultural memories to counter Hollywood’s inadequate representations, to inform future remembrances of Gullah culture.

Speculative fiction is a narrative mode uniquely equipped to provide accounts of “previously unrepresented history.” (Erhart, “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction,” 129.) Its preservation of cultural memories produces contemporary cultural materials that give voice to narratives historically silenced by colonial forces, thereby informing future cultural recollections. Dash repurposes cinematic tools to highlight the significance of the senses in cultural memories whilst providing radically new images through the elements of mise-en-scène, editing, sound, and performance.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erhart, Julia. “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 13, no. 2 (May 1, 1996): 116–31.

Marks, Laura U. “The Memory of the Senses.” In The Skin of the Film Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses, 194–242. Duke University Press: Durham , 2000.

Reclaiming Memory: The Role of Speculative Fiction in Daughters of the Dust

By Caitlyn Salter

There are no shortage of films in which the notion of a strict linear timeline is dissolved, however in Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, the concept of a linear past/present/future relationship is stripped away almost entirely. Memory is pulled into the present and characters are not haunted by the past, but by the future. Dash emphasises the importance of these shifts from the Western understanding of time, while also highlighting just how natural it is to conceive of events in this way. Throughout the film, the two techniques of superimposition and voiceover in particular can be said to highlight this absence of linearity and the collective experience which make up the central theme of the film.

Figure 1.

The way in which this film is edited is particularly significant. Editing already suggests some kind of arranging of time/events in a way that is not strictly linear, however the tendency towards superimposition via fade cuts in Daughters of the Dust is important in how it

demonstrates a peeling away of the structure of time in which the audience might expect. There is one sequence close to the middle of the film, wherein the Unborn Child speaks over a series of superimpositions of relatively unassuming shots. The sequence does start with a more straightforward cut from Nana Peazant to the natural scenery of the island, but the scenery gives way to a long-shot of a man on a bike, which then gives way to a shot of the whole family on the beach walking towards the camera. These shots are not particularly explicit with their meaning, but instead prompt the audience to release the idea of a physical present. And in this absence, the importance of memory becomes clear. As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the shifting from scene to scene blurs together, prompting the audience to consider how the periods of time might also synthesise with one another. It is almost as if the film is asking the audience to understand that though they might perceive the scenes in a linear format, due to how most of us automatically view films, there is a possibility where there is no such thing as a strictly linear form. It may appear that these scenes follow one another, but there is in fact, no undeniable proof that they do take place like this. The seconds spent on the island could take place at any point, the man on the beach is not recognisable as any one person shown throughout the film — these scenes could very well take place at any point in this family’s history, in this island’s history. As Julia Erhart states, Nana Peazant’s role is “both to interrupt myths about the “promise” of migration and to provide a link to images of an African past” (Julia Erhart, “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction,” Camera Obscura 13, no. 2, 1996.), who is to say that these are not images of that African past? Certainly, they could be images of the Peazants’ past — with the continual weaving together of different time periods, different memories, to fail to consider this potential could be missing a significant possibility. The mid-shot of Nana Peazant in Figure 1 may well be her at any point in the past decade or so. The thread that pulls the sequence together is the voice of an unborn child, an element which is firmly not in the concrete present.

Figure 2.

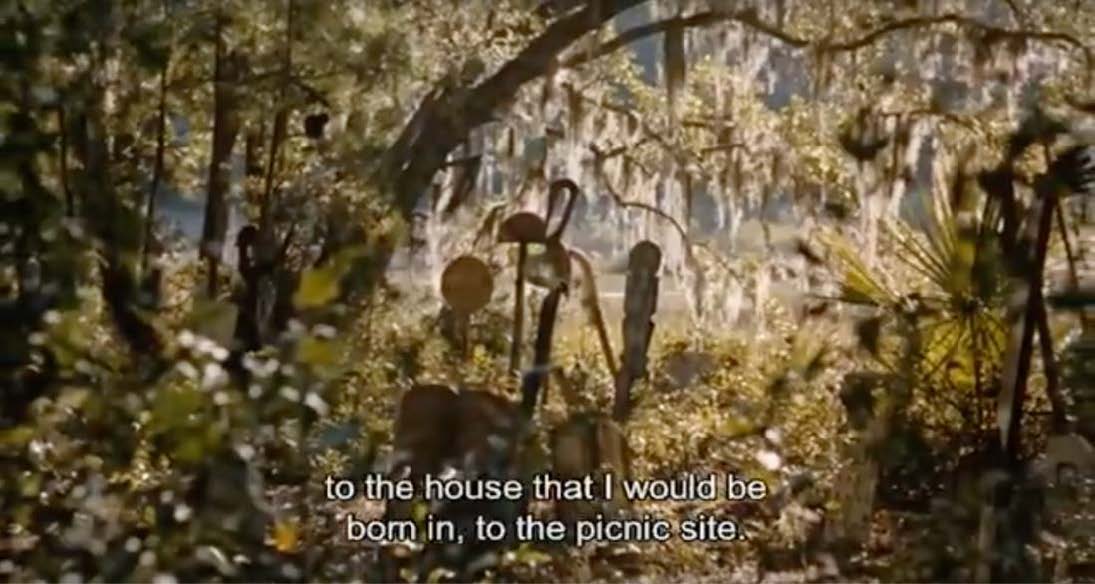

Figure 3.

It would be remiss now, to skip over the presence of the voiceover in Daughters of the Dust. Voiceover is a recurring element throughout the film, many characters are presented in this matter — specifically, Nana Peazant, Eula, and the Unborn Child. The Unborn Child is who speaks in this sequence and indeed, is a kind of narrator for the whole film. This presence

indicates to the audience that even if things appear as if they are a straightforward series of events, there is nothing that is not touched by the voice of the past or future. In this way, haunting, though generally considered as a lack of closure from the past, is transformed into what I would call a neutral persistence of the future. The Unborn Child can be said to be the ultimate neutral of the film: she has impacts on the family that can be seen as positive, but in truth, her role is to prompt the characters towards action. She is not a negative presence, nor is she a lack of closure that needs to be reconsidered — though she can be thought of as a “haunting”, she is not a “ghost” per se. Instead, Dash gives the audience a character who is relentless in a different sense, unable to be deterred in a way that indicates haunting, but doesn’t fulfil what might be anticipated. As shown in Figure 2, the Unborn Child speaks in the future tense: “to the house that I would be born in”. This future tense asks for trust in the future, perhaps from the characters, perhaps from the audience. The Unborn Child is a continuous sign of the fluctuation between past and future, meeting somewhere in the present; she pushes for consideration of the past through the way in which she “remember[s]”, but she also demands an acceptance of what is to come. In this way, Dash reminds the audience that in this case, if not many, any one period of time cannot be considered alone. There is always the potential to be haunted, from one direction or another. Moreover, this is not something to fear, but rather a natural and neutral part of life.

Figure 4.

It is this synthesis of trust in the future and prioritisation of the past that presents what might be called the thesis of the film: collective experience. Though there are characters who might be considered protagonists due to their relatively large amount of screen time, in the end, it is the collective experience of past, present and future that Dash seems to highlight throughout the entirety of the film. In this sequence, this becomes particularly clear. The transitions between the various shots prompt the idea that there is no true individual experience or understanding. Nana Peazant is a figure who is constantly emphasising the importance of understanding the collective experience of the past. The shot fades to the scenery of the island — nothing if not a capsule of the family who live/d on it. Fade again to the beach, an unidentifiable man, it doesn’t matter who it is, what matters is that there is a presence on the land that this family knows intimately, therefore he must be part of it (Figure 3). The final portion of this small sequence: the family, together. Laura Marks mostly speaks about the sensory aspects of Daughters of the Dust, which there is not time to cover here, but I would like to posit that her point that cinema such as this film moves from “excavation to transformation” and indeed “bears witness to the reorganization of the senses […] and the new kidneys of sense knowledges that become possible”2 is essential when considering this film in any capacity. Through the (visual) blurring of superimposed images and the (auditory) voiceover, the audience is pushed towards an understanding of the film that may not otherwise occur to them as a way to view people’s lived experiences. Dash almost overwhelms the audience with these elements, they are both incredibly explicit and yet require so much from a viewer and this is precisely the experience that Daughters of the Dust demands the viewer must have in order to understand the power of this collective experience.

As a whole then, Daughters of the Dust becomes a film in which the audience is pushed to reconsider how they wish to approach the ideas of memory and haunting. Memory as deeply intertwined with the present; haunting as something that can also come from the future. Dash, I believe, wants the audience to at least come away from the film thinking about these possibilities, even if they cannot wholly conceptualise them. In the near-excess of superimposition and voiceover, it can be said that this film demands respect for these possibilities — it isn’t possible to come to a conclusion in the time that one watches a film, but one must bear witness to a relentless non-linearity that they must then come away from. It is through this that there is an almost inescapable result of immersion, even for a short period of time, in something that is indeed, transformative.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Erhart, Julia. “Picturing What If: Julie Dash’s Speculative Fiction.” Camera Obscura 13, 2 (1996).

Marks, Laura. “The memory of the senses.” In The Skin of the Film. Duke University Press (2000).

Reclaiming Memory: The Role of Speculative Fiction in Daughters of the Dust

By Olivia Castree-Croad

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust uses the rich layering of sensory input to physicalise memories and evocations of the past. The ways in which these plural forms of sensory understanding are used against and in tandem with one another shifts the balance of the physical presence of the past’s place in the present. Often, competing forms of sensory input can create a present overwhelmed or haunted by a memory. However, when in moments when the materiality of the past does not threaten the materiality of the present, the use of non-visual information to invoke the past can create convergent moments in time, in which past and present coexist in the same place. When thinking of the Unborn Child and her place as both a rememberer-narrator and a ghost in her own narrative, the strength of memory against the present invites us to reconsider the temporal position of the entire film. In fact, notions of “past” and “present” as distinct categories are themselves troubled through the film’s use of continuity in modes of sense-memory and gustatory knowledge as forms of connection to history.

One prominent aspect of the layering of sensory information to imbibe a sense of the past into the physical place of the present, materialising memory, comes in the richly dimensioned soundtrack and audio of Daughters of the Dust. In this sequence, a prominent example is the layering of Viola’s recount to Mr Snead(?) of the naming conventions of Sea Island families, underscored with the steadily pulsing “tribal” musical motif which ebbs and flows throughout the film like breath. Viola’s assertion that despite it being “50 years since slavery”, families still use the same naming conventions they once did, naming their children “the day of the week or season in which they were born” demonstrates the continued presence of past habits in the lives and routines of the Gullah culture of the present. More than this, however, the musical underscore of this section of dialogue steadily begins to overtake Viola’s almost automatic listing of children’s nicknames. Her voice, divorced from her image and layered over Elijah in the graveyard (Fig. 1), shot in slow motion and at a lower frame rate to lend his movements the dreamlike quality of existing in a moment of unstable temporality, takes on an incantatory quality. The music and accompanying vocalisations rise almost in response to Viola’s invocation, as though she has called something very material out of the memory of the past contained in the children’s names, which now hangs over the present. That the music continues beyond the fading of her narration demonstrates the memory’s presence has become entirely divorced from the moment of her recollection.

Figure 1.

This is one of the most prevalent themes of Dash’s film, the process of sensory recollection as a kind of calling or casting or summoning of the past, which, once invoked, detaches itself from the individual, becoming a collective-memory experience, or a memory infused into the landscape. In this way, the shadow of the past over the present could be understood as a haunting, but this term carries negative connotations which don’t always consistently align with the film. Though histories of enslavement remain, dormant but present, in the lives of the Peazants, it is just as common for the sensuality of the mode of remembering to arise out of a pleasant state of being – the sequence where the children and their grandmother recall different Igbo words or phrases on the beach, for example – or to a family-related or domestic task – in this case, the naming of the children, though in other cases, related to the preparation of food.

Physicalising the past through the use of many different forms of sensory information creates a sense of the past’s being in the present, layering the past and the present over the top of one another in the same landscape. In this way, characters walk simultaneously through present reality and through the steps of memory as they live their lives, their actions paralleling memory-events in cyclical sequences in which the two extremely present sensory worlds of the past and the present come into contact and potentially conflict. In this sequence, Dash draws a connection between Elijah and the enslaved Igbo prisoners, after which Ibo landing is named, through parallel camera movements, panning first up Elijah’s body in the graveyard, then, at the same pace and

proximity, panning up the length of the floating Igbo sculpture in the water. Later, the connection between Elijah’s present and the events of the Ibo Landing which characterise the site’s past is realised in a spatial clash between two time periods. Once again, the music heralding the incursion of memory into the present underscores Eula’s voice reciting the story of the Ibgo retreat from Ibo Landing. Rather than being overpowered by the music of memory, as Viola’s voice is earlier on, Eulah acts as a knowing conduit between the past and the present, constructing the sensory information which acts as a physicalization of the past. Enacting the events of the story, Elijah’s walk across the water demonstrates a confluence of two times changing the face of the same space.

Figure 2.

The water (Fig. 2) appears barely an inch deep for Elijah, who walks and kneels before the Igbo statue, which appears halfway submerged. This spatial impossibility enables two time periods to exist physically in the same space, sitting against each other and distinctly interacting with each other and Elijah pushes the sculpture further out into the water. As well as this, these two conflicting spatial realities demonstrate the simultaneous presence of constructed memory and a less constructed “reality” over the presence: Elijah’s walk across the water enacts the events of a story, framed as the Igbo “going home” over the water, while the statue’s submersion reflects the reality of the event this story represents as a mass suicide. In the presence of both versions of the event, neither one is privileged over the other, the presence of one kind of memory and another equally strong in the characters’ interactions with the present.

This layering of sensory information to enable the coexistence of multiple times in one space can be understood as a rupture not only between present and past, but between present and future when considering the figure of the Unborn Child. However, given that the Unborn Child’s narration connects the vignettes of the film both chronologically and thematically, it could be argued that, rather than the Child’s presence acting as a bleed from the future into the present, she can instead be understood as a remembering agent in her own right, whose space in her own recollection is overpowered by the strength of the memory she conjures. In this way, the events of the entire film can be repositioned not as a present into which the viewer is situated, but as a memory so strong that the Unborn Child, the rememberer, appears ghostly when her presence colours her own recollection.

Figure 3.

If, as previously outlined, the past frequently overtakes and overpowers the voices of the film’s “present” in providing more concrete, recognisable, evocative sensory information to the viewer, the solid presences of the Pezant family against the ghostly figure of the Unborn Child lend themselves more strongly to the way memory is constructed in this film than they do to being figures of the present. If rather than being a figure from Eula’s future, Eula is a figure from the Child’s past, then they are able to interact with each other somewhat deliberately, as they do above as the Child runs into Eula dancing. Through the figure of the Child we can frame the events of the film as manifestations of memory, understanding the film’s function as a construction of what Paulla Ebron refers to as “public memory” (Ebron, 2014). Creating a public memory is a distinct process of remembering because “requires a specific departure from understandings of memory that assume a basis in personally experienced, remembered events” (Ebron, 2014), using a public space as a site upon which new “publics” can come to understand themselves and be understood. If Daughters of the Dust is understood as a recollection by the Unborn Child, the mode of memory it inhabits is inherently divorced from the individual, personal recollection of the Child by virtue of the events occurring before her birth.

Therefore, the ghostly aspects of the child in this sequence and throughout the film – her translucence, the fact that she is filmed, once again, with the dreamy low frame rate and slow motion which characterises temporal rupture in this film – softens her presence comparative to the strong physical presences of the rest of the Peazant family, demonstrating not only the strength of the memory over her present, but her place as only one of many storytellers, relating events which are themselves a series of recollections remembered collectively across the entire present Peazant family, passed to her generationally.

Given the examples above, sense-memory can be understood in Daughters of the Dust to construct an invasion of a distinct past into the present (Despite my above reframing of the film’s present as a construction of the Child’s past, in this essay I will continue to refer to the events of the film as “the present”, for the sake of clarity.), either overshadowing and drowning present action in the weight of the past, or converging two discrete points in time onto one site. However, interactions with food throughout the film provide a wealth of non-visual sensory information which exists firmly and totally within the sphere of the present. This is not to say that food does not provide a kind of sense-memory, connecting the present to the past – rather, it is to say that the repetitions of domestic activity such as meal preparations and communal dining present a view of past and present as one continuous state of being, rather than two distinct, though related, time periods. In this sequence, the musical motif of the past remains present, though somewhat muted, over the close, sumptuous shots of people serving, cutting, and eating food. As before, this audio signifies a connection between the actions of the present with a collective past, but the soundtrack is not the only non-visual form of sensory information presented to the viewer. The close shots of hands interacting with food provide a representation of Gullah sense-memory, encoded in the gustatory knowledge systems found, according to Laura Marks, across many African traditions. (4 Marks, 2000)

Figure 4

family, at any time, engaging in the same food-centred social activity. The preparing and sharing of food is not a distinct present action, rather a continuation of the same actions performed over and over again throughout generations. The invocation of a memory is an invocation of a separated past which does not exist here – the same food is still being eaten, the same knowledge encoded through the senses, the same communion occurring with little discrepancy to the way it has occurred for generations. The past and the present are totally unified as an uninterrupted flow of events across the same continuum.

Daughters of the Dust “translates into an audiovisual medium knowledges that have survived largely as oral history and sense memory” (Marks, 2000), intertwining alternative forms of knowing and recalling through its manipulation of different sensory knowledges and sense-memory to demonstrate numerous temporal relationships as the present is changed by (and changes in turn) the past.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ebron, Paulla A. “Site Of Memory 1: A Film Revival.” In Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales, ed. by De Cesari, Chiara, and Ann Rigney. De Gruyter, 2014.

Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film. Duke University Press, 2000.

Temporal Disturbance: Tracking Shots and Trauma in Hiroshima Mon Amour

By Julien Klettenberg

Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959) presents itself as a romantic drama, the story of two unnamed adulterous lovers in postwar Hiroshima, yet its thematic focus has far more to do with an examination of the revelation of trauma, largely through an innovative use of filmic devices such as the flashback. The following discussion will examine the filmmaker’s use of the flashback, setting and tracking shots in his exploration of memory and trauma. For Resnais, the flashback is not simply a “personal archive” (Maureen Cheryn Turim, Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History. (New York: Routledge, 1989): 2.), an opportunity to illuminate the present by reference to the past, with the two maintaining a simple continuity; rather, one might observe what Gilles Deleuze (1989) perceives, that “the present begins to float, struck with uncertainty, dispersed in the characters’ comings and goings or already absorbed by the past.” (Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, the Time Image. (London: Athlone, 1989), 121.)

Roger Luckhurst (2008) has declared that “Alain Resnais invented the traumatic flashback in Hiroshima Mon Amour.” (Roger Luckhurst, The Trauma Question. (London; Routledge, 2008): 185.) Commenting further on Resnais’ films, Luckhurst posits that Hiroshima Mon Amour forms part of a series, beginning with his work as an editor of documentary films and continuing into his career as a director with Nuit et Bruillard (1955), creating “a systematic experiment in exploring how cinematic form can represent traumatic, temporal disturbance in the wake of violence or war.” (Roger Luckhurst, The Trauma Question, 186.) Brett Kaplan (2021) adopts this view, and applies it, in discussing Hiroshima Mon Amour, to the example of the woman, glancing at her Japanese lover’s twitching hand as he sleeps, being plunged abruptly into the shocking memory of her dying German lover’s bloody twitching hand. (Brett Ashley Kaplan, “Too Painful to Forget, Too Painful to Remember: Ashes of Memory in Marguerite Duras and Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Duras’s La Douleur (1985).” Memory Studies 14, no. 4 (2021): 840.) This early scene could be said to act as something of a prelude to the lengthier flashbacks that occur in the clip that is being examined here, both in a narrative sense and in relation to the film’s broader examination of trauma and memory. In this instance, the memory is involuntary, with Kaplan noting its Proustian character (Brett Ashley Kaplan, “Too Painful to Forget, Too Painful to Remember”, 840-841.), and, as such, one can compare it to the later instance, when the woman, shown in a shot, reverse-shot medium close-up sequence across the table from her lover in a bar and about to describe the cellar, is thrown again to a sudden recollection of her dying lover (Figure 1).

![]()

Figure 1.

It is the “unbidden” nature of these involuntary memories that affords them their Proustian dimension (Brett Ashley Kaplan, “Too Painful to Forget, Too Painful to Remember”, 841.), and highlights their relationship with the woman’s past trauma, one that is reemerging in her visit to Hiroshima. Resnais also employs more subtle flashback techniques, the significance of which perhaps only become evident with repeated viewing, as in the image in Figure 2, to which the film cuts after a lengthy recollection by the woman of her clandestine meetings with her German lover, followed by her remark, “puis il est mort” (“then he died”).

Figure 2.

The meaning of this shot is left unexplained, until it is repeated later in the film and placed into context by the woman when she finally relates the killing of her German lover, by a sniper, at the moment when they were supposed to flee together to Bavaria. These flashes of memory are part of what Cathy Caruth (1996) describes as “the continual reappearance of a death she has not quite grasped, the reemergence, in sight, of her not knowing the difference between life and death.” (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996): 37.) In Caruth’s view (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 37-38.), it is the reconciliation of this difference, through her Japanese lover’s apparent adoption of her dead lover’s identity (“Quand tu es dans la cave, je suis mort?”) and the provision of a “when” to her traumatic memory, thus beginning an undoing of the “temporal disturbance”(Roger Luckhurst, The Trauma Question, 186.), and allowing her to finally recall the circumstances of his death.

Amedeo D’Adamo (2017) employs the notion of Dantean Space (drawing on the structure and characters of Dante Alighieri’s Inferno) in an analysis of the use of setting in the film, which might be seen to a useful tool in this instance. D’Adamo does not provide a concise definition for this framework, but he contends that “the story’s setting has become a projection of the character’s inner emotional drama, thus allowing us a powerful empathetic access to her inner emotional conflict through sensory, visual and aural means.” (Amedeo D’Adamo, Empathetic Space on Screen: Constructing Powerful Place and Setting. 1st ed. (Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2017): 19.) In D’Adamo’s view, the setting of the film becomes “a deep communicating medium of character.” (Amedeo D’Adamo, Empathetic Space on Screen, 62.) On the face of it, the film takes place in a newly reconstructed Hiroshima, just over a decade after the destruction of the city by an atomic bomb, yet, as Caruth notes, the focus of the film becomes the revelation of the woman’s traumatic history in the French city of Nevers, in the aftermath of its liberation from Nazi occupation. (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 27.) Resnais introduces the city of Hiroshima at the beginning of the film with images of the woman’s memories of a visit to various sites (a hospital, a memorial museum), graphic reconstructions of the aftermath of the bombing and its victims, and finally newsreel footage of the devastated city (the viewer’s first glimpse of the actual destruction, rather than as a reconstruction or model). It is a site of destruction, death and trauma, but it is a trauma that has not been experienced by either of the principal characters: for the woman, the destruction of Hiroshima had previously signified the end of the war (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 29.), and for the man, the viewer learns that it resulted in the death of members of his family, but that he was not present for this, being away fighting. (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 40.) Their trauma is of a more personal nature, and Caruth finds a parallel in the woman’s missing of the moment of her lover’s death (“for in missing the moment of his death, the woman is also unable to recognize the continuation of her life” (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 39.)) and the man’s absence, arguing that “through its very missing, his story, like hers, bears the impact of a trauma.” (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 40.)

However, as Luckhurst notes, after these initial scenes, the destruction of Hiroshima is referenced only obliquely: “through the traumatic memories the city provokes in the visiting French actress.” (Roger Luckhurst, The Trauma Question, 185.) Yet, before the woman finally recounts her experience in Nevers to her Japanese lover, Resnais inserts footage of the rebuilt Hiroshima, dissolving from a wide shot of the two lovers’ farewell embrace into an evening sequence of five brief images of the Ōta River (or one or more of its tributaries), which are notable for both their stillness (the camera is fixed and the only movement on screen is that of the river, or a distant neon sign or tram), and the anonymity of the Japanese people depicted, who are shown either from the back or, at best, in profile, and often out of focus. The sequence is approximately thirty-two seconds long, and Resnais cuts between each image, in an almost documentary style – something of a contrast to his use of dissolves, which give other scenes an almost hallucinatory quality. The opening shot of this sequence (Figure 3) is notable for its inclusion of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome): “the only structure left standing in the area where the first atomic bomb exploded on 6 August 1945.” (“Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome)”, UNESCO, accessed 12 September 2024, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/775)

Figure 3.

The depiction of the Memorial, emerging from the shadows of the riverbank, provides an instant and stark reminder of both time and place, and it serves, arguably, as an ideal distillation of Caruth’s view that the film is not merely about Hiroshima, but that it forms “a discourse spoken, as it were, on the site of a catastrophe.” (Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience, 34.) One is also reminded of D’Adamo’s Dantean view, above, of setting as a representation of individual trauma.

Of interest also is Resnais’ use of the tracking shot in Hiroshima Mon Amour, and its relationship to memory. Pierre Louis Spadone (1996) describes Resnais’ use of the tracking shot to define urban space: a “technical invention … based on a kind of meticulous surveying of the space being staged” (“invention technique s’appuie sur une sorte d’arpentage minutieux de l’espace mis en scene” (translated by Scholar GPT, https://chatgpt.com/g/g-kZ0eYXlJe-scholar-gpt, accessed 12 September 2024); Pierre-Louis Spadone, “Les reérages urbains d’Alain Resnais: des ‘espaces empreints de temps.’” Espaces et sociétés n°86, no. 3 (1996): 92.). He argues that it “establishes a relationship between the filmmaker’s eye, urban space, and the space of memory” (“établit une relation entre l’oeil du cinéaste, l’espace urbain et l’espace de la mémoire” (translated by Scholar GPT, https://chatgpt.com/g/g-kZ0eYXlJe-scholar-gpt, accessed 12 September 2024); Pierre-Louis Spadone, “Les reérages urbains d’Alain Resnais”, 92.). Spadone relates Resnais’ use of tracking shots particularly to his filming of urban spaces, and Emma Wilson (2006) discusses them in a similar manner, in the context of Hiroshima Mon Amour, describing the use of cross-cutting sequences of tracking shots of Hiroshima and Nevers, whilst the woman walks in Hiroshima, arguing that “The urban space … is now summoned as a reflection of her psyche” (Emma Wilson, Alain Resnais. (Manchester; Manchester University Press, 2006): 62-63.), suggesting a sense of the blurring of memory and reality in the combination of cross-cutting and tracking. Similarly, Spadone states that “the journey is a memory in action: in Alain Resnais’ creative work, the act of finding one’s bearings amounts to “giving a memory” to the characters and the locations of the action.” (“le cheminement est une mémoire en acte: l’acte de repérage, dans le travail créateur d’Alain Resnais, revient à “donner une mémoire” aux personnages et aux lieux de l’action.” (translated by Scholar GPT, https://chatgpt.com/g/g-kZ0eYXlJe-scholar-gpt, accessed 12 September 2024); Pierre-Louis Spadone, “Les reérages urbains d’Alain Resnais”, 109.) Central to all of this is Resnais’ use of the tracking shot, which can be seen in two extended instances of flashback in the clip being analysed here (the woman’s recollection of her meetings with her German lover and her description of Nevers and the Loire). If one extends the discussion initiated by Spadone and Wilson, it might be possible to view these two sequences from the same perspective, noting the use of tracking shots to highlight the depiction of memory. In addition, if one contrasts these two sequences with the stillness of the sequence of shots of the Ōta and Hiroshima at night, discussed above, and the fact that they are resolutely placed within the film’s narrative present, then the apparent link between the camera’s movement and memory becomes arguably more pronounced. The first of these sequence begins with two brief long shots of the woman, shown as an eighteen year old, riding her bicycle, before cutting to a lengthy tracking shot (Figure 4), which initially follows her progress on her bicycle, before the camera’s movement accelerates to the point where focus is lost, and finally coming to a rapid halt on a close-up rear view of her German lover, watching her arrival.

Figure 4.

Similarly, in a later sequence, the woman describes Nevers to her lover, who states that he can’t imagine it, and the viewer is shown a tracking shot of the Loire, while the woman speaks, with the movement of the camera evoking a sense of her personal memory.

Alain Resnais’ use of flashbacks, tracking shots and setting in Hiroshima Mon Amour are not mere aesthetic choices, but are rather indelibly linked to his wider project of an exploration of trauma in the aftermath of catastrophe. Setting finds meaning in a Dantean analysis of space, whereby it might be viewed as representative of the characters’ emotional state. The flashback and tracking shot are employed variously as complex signifiers of memory and trauma. A brief study of Resnais’ use of the tracking shot has been attempted, but an opportunity exists for further examination of his use of the tracking shot as a signifier, particularly in a comparative analysis across his other films, beginning with Nuit et Bruillard.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Caruth, Cathy. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

D’Adamo, Amedeo. Empathetic Space on Screen: Constructing Powerful Place and Setting. 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2017.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2, the Time Image. London: Athlone, 1989.

Kaplan, Brett Ashley. “Too Painful to Forget, Too Painful to Remember: Ashes of Memory in Marguerite Duras and Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Duras’s La Douleur (1985).” Memory Studies 14, no. 4 (2021): 834–55.

Luckhurst, Roger. The Trauma Question. London; Routledge, 2008.

Spadone, Pierre-Louis. “Les reérages urbains d’Alain Resnais: des ‘espaces empreints de temps.’” Espaces et sociétés n°86, no. 3 (1996): 89–110.

Turim, Maureen Cheryn. Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History. New York: Routledge, 1989.

UNESCO, “Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome)”, accessed 12 September 2024, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/775

Wilson, Emma. Alain Resnais. Manchester; Manchester University Press, 2006.

![]()

![]() We acknowledge Australia’s First Nations People as the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land, and pay respect to the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, upon whose Country SFF are based.

We acknowledge Australia’s First Nations People as the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land, and pay respect to the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, upon whose Country SFF are based.

We honour the storytelling and culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia.